Alex Maskara

Thoughts, Stories, Imagination of Filipino American Alex Maskara

Welcome

Short Stories

~

The Last of the Baluga

O Caca, O Caca

Cabalat capaya

Sabian mu nang tutu

Nung ena ca bisa

Ceta pu cecami

Dacal lang baluga

Mangayap la ceca

Biasa lang mamana.

(O Brother, O Brother,

whose skin is the color of papaya,

tell me at once

if you no longer wish to fight.

Because where I come from,

I can gather many Baluga—

far better than you

with bows and arrows.)

------

I am Pandaca, named after the second smallest fish in the world. I wear the name with equal shame and pride. It tells the truth about me before my body does: I am small, mountain-born, and easily overlooked.

I was born in Mariveles and wandered south as a boy until I settled on the slopes of Pinatubo. You know what happened there. When the mountain erupted, I moved again—to Arayat—because I am Baluga, and the mountains have always been my home.

You prefer to imagine me as a silhouette: naked except for a g-string, bow lifted, arrow drawn, frozen forever against the sky. Or playing a nose flute in a tree beneath a full moon. I exist for you as an image, not as a man. An anito—useful for stories, harmless because I am distant.

You are not wrong. I was once exactly that. And your blood remembers me even if your mind denies it.

I was here before you. I crossed land bridges when the sea still slept. I planted the first seeds in this volcanic soil. I did not fight when others arrived—first from Sumatra, then from the Malay Peninsula. I stepped aside and climbed higher. The mountains were sacred to us. They belonged to Sinukuan, our goddess. Civilization never tempted me. The forest was enough.

I bartered meat for salt, rice for cloth. That was our agreement with the lowlands. But when the forest was stripped bare and the animals vanished, I lost everything—food, shelter, dignity, even my right to remain. You did not stop until we were nearly gone.

Now I sit in one of the last trees on this mountain. Below me, the land is shaved flat, wide enough to see the city miles away. You call this progress. You erase centuries in minutes and sleep soundly at night.

From your balconies—in Switzerland, America, Baguio, Tagaytay—you drink and look out at mountains you no longer touch. Meanwhile, families like mine descend from the slopes, knocking on doors, begging for food, discovering that even those with houses are starving.

If you still imagine me on a cliff, let me remain there forever in your dreams. You will never see forests again. These mountains will become subdivisions. And when my generation ends, I will vanish with it.

Yes, I am alive. But survival is not life. I remember when our children laughed, when leaves whispered overhead, when the land welcomed us wherever we went. Trees were roofs. Birds laid eggs freely. Sinukuan watched.

Now our flutes are silent. Our bows are useless. I hold this tree as if it were a dying relative. We are both waiting.

Her spirit is young. She is searching for her mother, cut down days ago. Her grandparents—trees older than memory—fell without a sound, too shocked to cry. I try to soothe her, but the chainsaws are already singing.

I will not leave her. Without her, I do not exist.

I close my eyes and hum the old songs—memories carried in blood since the beginning of time. I see our people walking the mountains without fear. I see abundance so natural it felt eternal. This land, once blessed, is dying.

There is so much I want to say before I die with this tree.

It does not take brilliance to heal what you destroyed. This mountain needs trees—and to be left alone. Nothing more.

But you have chosen another way.

The men arrive with bulldozers. They shout the same words as before: “Get down from the trees, you monkeys.” This time, I am not afraid.

I will let my body scatter across this emptied land.

This is the last thing I can give.

And I know—no one will care.

-------

Historical and Cultural Notes

Baluga / Aeta

“Baluga” is a Kapampangan term often used to refer to the Aeta—one of the oldest indigenous groups in the Philippines. They are Negrito peoples, characterized by dark skin, curly hair, and short stature. Historically semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, they lived sustainably in forests long before Austronesian settlers arrived.

Land Bridges and Early Settlement

The story references prehistoric land bridges that once connected the Philippine archipelago to mainland Asia during the Ice Ages. Archaeological and genetic evidence supports the presence of Negrito populations in the Philippines tens of thousands of years ago, predating later waves of Austronesian migration.

Mount Pinatubo

The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo was one of the largest volcanic eruptions of the 20th century. It devastated Aeta communities, many of whom were permanently displaced. Resettlement programs often failed to account for indigenous lifeways, leading to poverty, cultural erosion, and dependence.

Mount Arayat

Mount Arayat, in Pampanga, is a solitary volcanic mountain long associated with Kapampangan mythology. It is traditionally considered a sacred place and a refuge—both physically and spiritually—for indigenous peoples pushed out of lowland areas.

Sinukuan

Sinukuan (also spelled Sínukuan or Aring Sinukuan) is a pre-colonial Kapampangan deity associated with Mount Arayat. Often portrayed as a guardian spirit or mountain god, Sinukuan represents balance, fertility, and the sacredness of the land—values central to indigenous cosmology.

Anito

“Anito” refers to ancestral spirits or nature deities in pre-colonial Philippine belief systems. In the story, the narrator becomes an “anito” in the modern imagination—reduced to myth, stripped of living presence.

Deforestation and Displacement

Large-scale logging, mining, and land conversion—especially during the 20th century—led to massive forest loss in Central and Northern Luzon. Indigenous peoples were among the first displaced, often criminalized for practicing subsistence lifestyles in lands reclassified as “private” or “development zones.”

The Monkey Slur

The insult shouted by bulldozer drivers echoes real historical dehumanization of indigenous peoples in the Philippines. Such language justified land seizure and violence by framing natives as less than human.

2026-02-01 22:11:41

shortstories

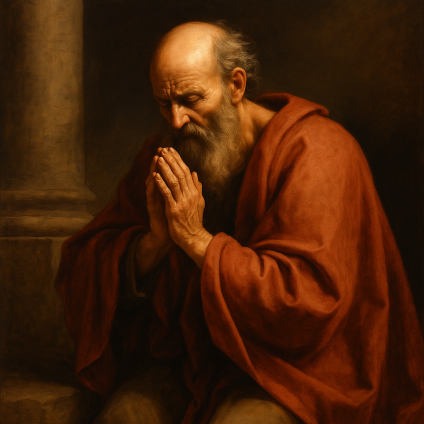

In the quiet town of Amherst, Massachusetts, where maple leaves turned gold each autumn and robins sang at dawn, lived a man named Alfred Reyes. Nearly 63, Alfred was no longer a man in a hurry. The years had gently pruned his once-bustling life down to silence and solitude—two things he now embraced with reverence.

Alfred sat by the window of his modest cottage overlooking a thicket of pine, oak, and the stubborn patch of wild jasmine he never managed to control. The morning sunlight glinted off the dew resting on the hedges, and the scent of jasmine lingered faintly in the air. He sighed, staring out at his overgrown backyard. The vines were winning again.

Yet today, as with many days now, his thoughts turned not to landscaping or errands, but to the inner garden he was tending—his soul.

“I didn’t understand it before,” he muttered to himself, gripping his warm mug of green tea. “The Holy Spirit. Everyone talked about it like some wind you feel at church… but it’s more subtle than that.”

He paused, his voice catching. “It’s taken me a lifetime to hear it.”

That afternoon, Jim, his housemate and the closest thing he had to family now, wandered in from the porch.

“Cleared the vines again?” Jim asked, peering through the screen door.

Alfred chuckled, sweat on his brow. “I tried. They grow faster than my resolve. But I suppose that’s how temptation works too.”

Jim leaned against the doorway, arms crossed. “Temptation?”

“The kind that tells you to get in your car and just drive,” Alfred said. “Looking for what’s never really there.”

Jim nodded, understanding without asking.

There were times when Alfred’s old fantasies still whispered to him—early morning drives to forgotten gas stations, fleeting encounters under city lights, the lure of aimless escape. But now, such things felt distant, like a life lived by someone else.

“I used to chase wild things,” Alfred told Jim later that evening, “thinking I’d find meaning. But all I got was exhaustion.”

He looked out again at the backyard, where his small bamboo colony swayed. “You know what saved me today?”

“What?”

“I was about to head out, start one of those pointless drives. But then I saw the vines—those damn vines—and I heard it. The voice. The nudge. ‘Tend what you have.’ Not ‘chase what you lack.’”

Jim smiled faintly. “Maybe that’s the Spirit.”

“I think so.”

Each day now brought decisions—not grand ones, but small, persistent forks in the road. Read or scroll? Sleep or drive? Pray or despair?

It wasn’t about moral victory. It was about peace. And Alfred was learning that peace didn’t come from achievement or praise, or even from being needed. It came from alignment. From choosing what his spirit yearned for.

He no longer feared sleep like he used to, as if rest was failure. “Sleep is a sacrament,” he whispered once while resting in the backyard, arms behind his head, the hum of bees and rustling trees his lullaby. “I wasted decades thinking I had to be always alert. Always needed.”

His thoughts often turned to his departed siblings—his brother and sister, whose illnesses had once filled his days with worry. Their passing was a sorrow he carried gently now, like a photo in his wallet.

“I was their safety net,” he told Jim over breakfast one morning. “That’s why I stayed healthy. That’s why I didn’t rest. I was afraid that if I stopped, everything would collapse.”

“And now?” Jim asked.

“Now?” Alfred smiled. “Now I rest. Because I’m no longer afraid. The Spirit has kept His promise.”

He walked daily. Five miles if he could. Afterward, he trimmed back snake plants and jasmine, feeling their stubborn roots echo the stubborn habits he was also learning to prune. Sometimes meditation led to drowsiness, and he welcomed it now. Other times, it was reading that steadied him, or fiddling with one of his many computers.

“I’ve got Ubuntu, Mac, Windows… even a miniPC,” he laughed. “But still, nothing satisfies like a good sentence in a good book.”

“You’re becoming a monk,” Jim teased.

“Maybe,” Alfred said. “But a monk with Wi-Fi.”

One morning, after another long walk through the Amherst conservation trails, Alfred stood quietly beside a patch of wild grasses taller than himself. Dragonflies shimmered above them like little angels. In that moment, he whispered a prayer—not of pleading, but of thanks.

He knew life was winding down. The body told him that in new aches each day. But the Spirit within… that still flickered with a light brighter than before.

“I’m nearly invisible now,” he wrote in his journal that night, “and maybe that’s a blessing. The world has stopped asking things of me. Now I can ask something of it: to show me beauty, stillness, and grace.”

Outside, a soft wind blew through the pines. Somewhere in the woods, a woodpecker tapped patiently. Alfred closed the journal and whispered one final line:

“It is not what I do anymore, but how I rest that honors God.”

And then he slept.

2025-07-25 01:37:41

shortstories

The Last of the Baluga

The Last of the Baluga

O Caca, O Caca

Cabalat capaya

Sabian mu nang tutu

Nung ena ca bisa

Ceta pu cecami

Dacal lang baluga

Mangayap la ceca

Biasa lang mamana.

(O Brother, O Brother,

whose skin is the color of papaya,

tell me at once

if you no longer wish to fight.

Because where I come from,

I can gather many Baluga—

far better than you

with bows and arrows.)

------

I am Pandaca, named after the second smallest fish in the world. I wear the name with equal shame and pride. It tells the truth about me before my body does: I am small, mountain-born, and easily overlooked.

I was born in Mariveles and wandered south as a boy until I settled on the slopes of Pinatubo. You know what happened there. When the mountain erupted, I moved again—to Arayat—because I am Baluga, and the mountains have always been my home.

You prefer to imagine me as a silhouette: naked except for a g-string, bow lifted, arrow drawn, frozen forever against the sky. Or playing a nose flute in a tree beneath a full moon. I exist for you as an image, not as a man. An anito—useful for stories, harmless because I am distant.

You are not wrong. I was once exactly that. And your blood remembers me even if your mind denies it.

I was here before you. I crossed land bridges when the sea still slept. I planted the first seeds in this volcanic soil. I did not fight when others arrived—first from Sumatra, then from the Malay Peninsula. I stepped aside and climbed higher. The mountains were sacred to us. They belonged to Sinukuan, our goddess. Civilization never tempted me. The forest was enough.

I bartered meat for salt, rice for cloth. That was our agreement with the lowlands. But when the forest was stripped bare and the animals vanished, I lost everything—food, shelter, dignity, even my right to remain. You did not stop until we were nearly gone.

Now I sit in one of the last trees on this mountain. Below me, the land is shaved flat, wide enough to see the city miles away. You call this progress. You erase centuries in minutes and sleep soundly at night.

From your balconies—in Switzerland, America, Baguio, Tagaytay—you drink and look out at mountains you no longer touch. Meanwhile, families like mine descend from the slopes, knocking on doors, begging for food, discovering that even those with houses are starving.

If you still imagine me on a cliff, let me remain there forever in your dreams. You will never see forests again. These mountains will become subdivisions. And when my generation ends, I will vanish with it.

Yes, I am alive. But survival is not life. I remember when our children laughed, when leaves whispered overhead, when the land welcomed us wherever we went. Trees were roofs. Birds laid eggs freely. Sinukuan watched.

Now our flutes are silent. Our bows are useless. I hold this tree as if it were a dying relative. We are both waiting.

Her spirit is young. She is searching for her mother, cut down days ago. Her grandparents—trees older than memory—fell without a sound, too shocked to cry. I try to soothe her, but the chainsaws are already singing.

I will not leave her. Without her, I do not exist.

I close my eyes and hum the old songs—memories carried in blood since the beginning of time. I see our people walking the mountains without fear. I see abundance so natural it felt eternal. This land, once blessed, is dying.

There is so much I want to say before I die with this tree.

It does not take brilliance to heal what you destroyed. This mountain needs trees—and to be left alone. Nothing more.

But you have chosen another way.

The men arrive with bulldozers. They shout the same words as before: “Get down from the trees, you monkeys.” This time, I am not afraid.

I will let my body scatter across this emptied land.

This is the last thing I can give.

And I know—no one will care.

-------

Historical and Cultural Notes

Baluga / Aeta

“Baluga” is a Kapampangan term often used to refer to the Aeta—one of the oldest indigenous groups in the Philippines. They are Negrito peoples, characterized by dark skin, curly hair, and short stature. Historically semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, they lived sustainably in forests long before Austronesian settlers arrived.

Land Bridges and Early Settlement

The story references prehistoric land bridges that once connected the Philippine archipelago to mainland Asia during the Ice Ages. Archaeological and genetic evidence supports the presence of Negrito populations in the Philippines tens of thousands of years ago, predating later waves of Austronesian migration.

Mount Pinatubo

The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo was one of the largest volcanic eruptions of the 20th century. It devastated Aeta communities, many of whom were permanently displaced. Resettlement programs often failed to account for indigenous lifeways, leading to poverty, cultural erosion, and dependence.

Mount Arayat

Mount Arayat, in Pampanga, is a solitary volcanic mountain long associated with Kapampangan mythology. It is traditionally considered a sacred place and a refuge—both physically and spiritually—for indigenous peoples pushed out of lowland areas.

Sinukuan

Sinukuan (also spelled Sínukuan or Aring Sinukuan) is a pre-colonial Kapampangan deity associated with Mount Arayat. Often portrayed as a guardian spirit or mountain god, Sinukuan represents balance, fertility, and the sacredness of the land—values central to indigenous cosmology.

Anito

“Anito” refers to ancestral spirits or nature deities in pre-colonial Philippine belief systems. In the story, the narrator becomes an “anito” in the modern imagination—reduced to myth, stripped of living presence.

Deforestation and Displacement

Large-scale logging, mining, and land conversion—especially during the 20th century—led to massive forest loss in Central and Northern Luzon. Indigenous peoples were among the first displaced, often criminalized for practicing subsistence lifestyles in lands reclassified as “private” or “development zones.”

The Monkey Slur

The insult shouted by bulldozer drivers echoes real historical dehumanization of indigenous peoples in the Philippines. Such language justified land seizure and violence by framing natives as less than human.

2026-02-01 22:11:41

shortstories

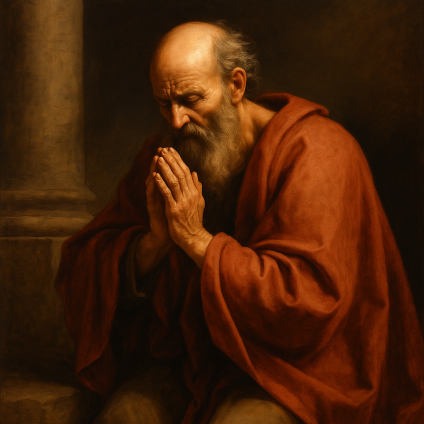

The Quiet Redemption

In the quiet town of Amherst, Massachusetts, where maple leaves turned gold each autumn and robins sang at dawn, lived a man named Alfred Reyes. Nearly 63, Alfred was no longer a man in a hurry. The years had gently pruned his once-bustling life down to silence and solitude—two things he now embraced with reverence.

Alfred sat by the window of his modest cottage overlooking a thicket of pine, oak, and the stubborn patch of wild jasmine he never managed to control. The morning sunlight glinted off the dew resting on the hedges, and the scent of jasmine lingered faintly in the air. He sighed, staring out at his overgrown backyard. The vines were winning again.

Yet today, as with many days now, his thoughts turned not to landscaping or errands, but to the inner garden he was tending—his soul.

“I didn’t understand it before,” he muttered to himself, gripping his warm mug of green tea. “The Holy Spirit. Everyone talked about it like some wind you feel at church… but it’s more subtle than that.”

He paused, his voice catching. “It’s taken me a lifetime to hear it.”

That afternoon, Jim, his housemate and the closest thing he had to family now, wandered in from the porch.

“Cleared the vines again?” Jim asked, peering through the screen door.

Alfred chuckled, sweat on his brow. “I tried. They grow faster than my resolve. But I suppose that’s how temptation works too.”

Jim leaned against the doorway, arms crossed. “Temptation?”

“The kind that tells you to get in your car and just drive,” Alfred said. “Looking for what’s never really there.”

Jim nodded, understanding without asking.

There were times when Alfred’s old fantasies still whispered to him—early morning drives to forgotten gas stations, fleeting encounters under city lights, the lure of aimless escape. But now, such things felt distant, like a life lived by someone else.

“I used to chase wild things,” Alfred told Jim later that evening, “thinking I’d find meaning. But all I got was exhaustion.”

He looked out again at the backyard, where his small bamboo colony swayed. “You know what saved me today?”

“What?”

“I was about to head out, start one of those pointless drives. But then I saw the vines—those damn vines—and I heard it. The voice. The nudge. ‘Tend what you have.’ Not ‘chase what you lack.’”

Jim smiled faintly. “Maybe that’s the Spirit.”

“I think so.”

Each day now brought decisions—not grand ones, but small, persistent forks in the road. Read or scroll? Sleep or drive? Pray or despair?

It wasn’t about moral victory. It was about peace. And Alfred was learning that peace didn’t come from achievement or praise, or even from being needed. It came from alignment. From choosing what his spirit yearned for.

He no longer feared sleep like he used to, as if rest was failure. “Sleep is a sacrament,” he whispered once while resting in the backyard, arms behind his head, the hum of bees and rustling trees his lullaby. “I wasted decades thinking I had to be always alert. Always needed.”

His thoughts often turned to his departed siblings—his brother and sister, whose illnesses had once filled his days with worry. Their passing was a sorrow he carried gently now, like a photo in his wallet.

“I was their safety net,” he told Jim over breakfast one morning. “That’s why I stayed healthy. That’s why I didn’t rest. I was afraid that if I stopped, everything would collapse.”

“And now?” Jim asked.

“Now?” Alfred smiled. “Now I rest. Because I’m no longer afraid. The Spirit has kept His promise.”

He walked daily. Five miles if he could. Afterward, he trimmed back snake plants and jasmine, feeling their stubborn roots echo the stubborn habits he was also learning to prune. Sometimes meditation led to drowsiness, and he welcomed it now. Other times, it was reading that steadied him, or fiddling with one of his many computers.

“I’ve got Ubuntu, Mac, Windows… even a miniPC,” he laughed. “But still, nothing satisfies like a good sentence in a good book.”

“You’re becoming a monk,” Jim teased.

“Maybe,” Alfred said. “But a monk with Wi-Fi.”

One morning, after another long walk through the Amherst conservation trails, Alfred stood quietly beside a patch of wild grasses taller than himself. Dragonflies shimmered above them like little angels. In that moment, he whispered a prayer—not of pleading, but of thanks.

He knew life was winding down. The body told him that in new aches each day. But the Spirit within… that still flickered with a light brighter than before.

“I’m nearly invisible now,” he wrote in his journal that night, “and maybe that’s a blessing. The world has stopped asking things of me. Now I can ask something of it: to show me beauty, stillness, and grace.”

Outside, a soft wind blew through the pines. Somewhere in the woods, a woodpecker tapped patiently. Alfred closed the journal and whispered one final line:

“It is not what I do anymore, but how I rest that honors God.”

And then he slept.

2025-07-25 01:37:41

shortstories